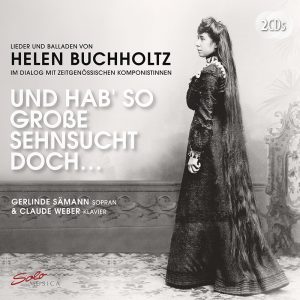

Helen Buchholtz

Helen Buchholtz (1877-1953)

Helen Buchholtz (1877-1953)

Charlotte Helena Buchholtz was born on 24th November 1877 in Esch-sur-Alzette, a small city in the south of Luxembourg. Her father, Daniel Buchholtz, was an ironmonger but also traded in household utensils and building materials. On top of that, he was the founder of the very successful Buchholtz Brewery. Little is known about Helen Buchholtz’s early musical education. According to her nephew, François Ettinger, she was interested in music, literature and art from a very young age and was taught the piano, the violin, music theory and composition.

As neither the music conservatory in Esch, nor the one in Luxembourg-City existed at the time, the only way to acquire a musical education was by taking private lessons or by joining a music association or choir. In those days, such associations open to women were rare. There were numerous music bands in Luxembourg but most of them were brass bands with a heavily military repertoire, which only accepted male members and this until well into the 20th century. Women were much luckier with choirs which had opened up to them in the 19th century already. Before then, these had also only been exclusively reserved to men. The Saint-Joseph Cäcilienverein in Esch, founded in 1815, was a mixed choir from the 1870s onwards and also acted as an institution that provided music teaching and training. We can assume, without the shadow of a doubt, that Helen Buchholtz’s talent was encouraged by other members of the family, especially since her father and uncle belonged to the circle of local music enthusiasts. The brothers also entertained a close friendship with Felix Krein (1831-1888), the most famous musician in Esch at the time and possibly the young girl’s first music teacher.

As was the custom among the aristocratic and bourgeois families of the time, Helen Buchholtz – like her sisters – attended the Pensionnat des Mesdames Métro-Bastien, a girls’ boarding school in Longwy (France), after her primary school education in Esch. At such 19th-century girls’ boarding schools, musical education had a firm place in the curriculum, although the teaching thereof was not supposed to go beyond the ‘female sphere’, meaning that the musical skills they were taught were only aimed at providing entertainment and relaxation. After returning from Longwy, Helen Buchholtz lived in her parental home, where she spent her time playing music and, eventually, trying her hand at composing.

Industrialisation made the number of inhabitants in Esch soar from 2000 in 1870 to 24,000 in 1913, which resulted in a rise and increase in variety of cultural events in Esch. At that time, music-making in private homes was still very popular and important, thus it can be assumed that Helen Buchholtz delighted audiences with her performances on such social occasions at regular intervals.

Industrialisation made the number of inhabitants in Esch soar from 2000 in 1870 to 24,000 in 1913, which resulted in a rise and increase in variety of cultural events in Esch. At that time, music-making in private homes was still very popular and important, thus it can be assumed that Helen Buchholtz delighted audiences with her performances on such social occasions at regular intervals.

In 1910, her father died. His son and son-in-law took over the management of the brewery, of which Helen Buchholtz held a quarter of the shares until her death. Her nephew, François Ettinger points out that ‘Helen Buchholtz was a woman of means who could provide for herself and hence, remain independent’. This financial safety net did indeed make the 33-year-old an independent woman overnight and allowed her to take her own decisions regarding her fate, like the decision to make music the centre of her life despite adverse conditions. On 2nd April 1914, she married the German doctor Bernard Geiger (1954-1921) in Metz and the couple moved to Wiesbaden. Ettinger: ‘Her dream of living in a big mundane city became reality. Wiesbaden, with its internationally renowned thermal baths, was also a cultural hub with its opera, theatre and concert halls – all which Helen Buchholtz had always wished for was now within her grasp. The music lover delved into the artistic and musical atmosphere of the city, which she enjoyed to the utmost.’ Ettinger adds that Buchholtz and her husband had agreed not to have children so that she could devote all her time to composing music.

Shortly after their move to Germany, World War I broke out. Helen Buchholtz used to maintain a steady correspondence with her music-loving brother-in-law but only seven correspondence cards from that period have survived. Surprisingly, however, music and Buchholtz’s musical work and studies rather than the war, everyday life in both Luxembourg and Wiesbaden under the occupation, food shortages and the inflation were the topics raised in these cards. From that correspondence, one can conclude that the musician acquired her skills to a certain extent autodidactically, as she wasn’t one of the very rare women who had gained access to study composition at one of the music conservatoires. She did, however, throughout her life, collaborate with other musicians. One of them was Berlin-born Gustav Kahnt (1848-1923), a retired conductor of the Luxembourg military music band, who taught music composition in Luxembourg-City. When she lived in Wiesbaden, she sent Kahnt her compositions, which he looked over, corrected and suggested improvements for. In general, he qualified her work as ‘very good and worthy of public recognition’. The composer acknowledged a number of Kahnt’s recommendations, but often refused to take on the role of the submissive student and ignored the advice. A final draft of her compositions was drawn up and sent to Luxembourg to print. The Felix Krein publishing house brought out five of her Lieder based on texts by Lucien Koenig. It has to be said that all her compositions were published under her maiden name. Later, the A. Ernst Musikalienhandlung in Wiesbaden published her two Lieder Die rote Blume (The Red Flower) and Die alte Uhr (The Old Clock), as well as an Ave Maria.

Bernard Geiger died unexpectedly in 1921. Helen Buchholtz seems to have processed this loss in her music compositions as a number of her songs deal with death, loss and abandonment. As her work is, however, mostly undated, a link between her biography and her music is purely speculative. After Geiger’s death, Buchholtz returned to Luxembourg and bought a small villa in Limpertsberg, a beautiful area in Luxembourg-City renowned for its fine rose-growing tradition. François Ettinger remembers that, ‘after her return in the 1920s, Buchholtz turned her attention to Luxembourg society, in particular to musicians and poets, like Batty Weber and his wife (the author Emma Weber-Brugmann), Fernand Mertens, etc.’

After Gustav Kahnt’s death in 1923, Helen Buchholtz continues her studies briefly with Jean-Pierre Beicht (1869-1925), who worked in Luxembourg as an organist, a music and song teacher, a choir conductor and composer. Beicht dies in 1925 and, as a result, she starts working with Fernand Mertens (1872-1957), a successful Luxembourg composer of Belgian origin. At the time, Mertens was the conductor of the Luxembourg military music band and taught solfeggio, theory of harmony and counterpoint. Although she spent the thirty remaining years of her life in Luxembourg, she only published six more compositions during that time: two Luxembourg Lieder after texts by Willy Goergen, the Lied Do’deg Dierfer as well as three male-voice choruses in German.

Helen Buchholtz died on 22nd October 1953, shortly before her 76th birthday, completely unrecognized as a composer. After her death, her nephew François Ettinger saved her music scores – which had already been packed into big bags to be burned – from the flames and stored them in two big suitcases in his house, where they were left for a very long time. I was lucky to discover them there in 1998. Nowadays, they are available to the public from the Helen Buchholtz Archive at CID-Fraen an Gender in Luxembourg-City.